By Hannah Tennant, Guest contributor

“Tennant!” a deep voice boomed. As I heard my last name, I stepped forward, and handed my driver’s license to the correctional officer through a slot at the bottom of the window he was staring at me through. Taking my license in his hand, he eyed me carefully, sizing me up. I was not allowed to wear blue, could not wear pants that were too tight, could not wear a shirt that clung to any curves; nothing to allude to the fact that there was a woman standing before him. I braced myself, praying not to relive the mortifying experience I had had a few weeks prior — the CO had taken one glance at me and announced, loudly, for all my classmates to hear: “Cleavage! I see cleavage!” The high-necked shirt that I had worn on that particular day was apparently too thin, and the outline of my breasts was still visible in the right light.

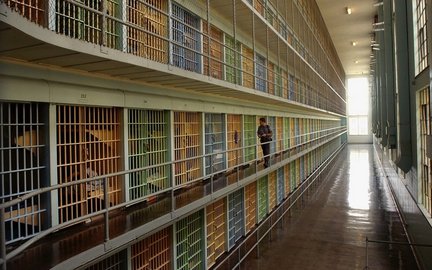

Today, however, the CO simply filed away my license and passed back to me a bright red visitor’s pass. “All set,” he said, and called out another classmate’s name. I silently clipped the pass onto my shirt collar and filed back in line behind my classmates. A few minutes later, the gate clanked and lurched to the right, back into the wall. We were processing through the second of three gates that would lead us into the heart of Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP), an all-male maximum security prison.

About nine weeks earlier, I had stood in the exact same position, filled with anticipation, and if I was honest with myself, fear. I had signed up to participate in a nationwide program called Inside Out. Once a week, for 10 weeks, I would travel with 10 other classmates up to Salem, Oregon, and take a college course with 11 inmates of OSP. On the first day as I waited in line and processed through prison, I had no idea what to expect. I knew that maximum security meant that these men had committed serious crimes – as serious as murder? How do you interact with murderers? What does small talk look like? Sorry you’ve been in this cement cell the last 30 years, but I have to tell you traffic was pretty brutal getting up here. I figured it couldn’t be too uncomfortable though, since we would probably just be listening to our professor lecture the whole time anyways. This was my first inaccurate assumption.

That first day, I walked into the classroom where we would spend the next 10 weeks with my fellow Outside students (those of us who were not inmates were considered to be “Outside”; they were “Inside”), and our professor instructed us to make two large circles with the chairs. The larger circle would face inward, and the second, smaller circle would face the outer chairs, with their backs to the center of the circle. We would be doing an activity called “Wagon Wheel,” she told us. The Outside students would sit in the smaller circle, facing the outer chairs. Once the inmates arrived, we would talk in pairs about whatever subject our professor posed to us, and after about two minutes she would instruct the Inside students to rotate. It was like speed-dating, but for college students and felons. We all took our spots and waited anxiously for the inmates to arrive.

After a few moments, a blonde man with bright blue eyes and a crew cut walked through the door, a notebook tucked under his arm. He was wearing a dark blue t-shirt that was tucked into baggy blue jeans with “Property of Oregon State Penitentiary” and the Oregon Crest stamped in bright orange on his thigh. He was wearing pristine Timberland boots, and walked with confidence. I was seated in the corner of the classroom farthest away from the door, hoping this would bide me time until I had to participate in the small talk. But of course, he walked straight for me, and took the chair opposite mine. “Hi!” he said. “I’m Brian.* What’s up?”

For the next few minutes, as the rest of the inmates slowly filtered in, Brian and I chatted. He seemed to feel much more comfortable than I did, and asked me about what I studied, and what I liked to do for fun. He offered up information about himself; told me that he’d been taking classes through this program for many years, and that he was president of the Lifers Club. I nodded along and smiled, like I have these sorts of conversations daily, while mentally putting together that this meant he would be in prison for life, and that therefore he was likely in for murder, or something else equally serious. My brain struggled to catch up with the information that I was receiving: this man sitting no more than six inches across from me had just informed me that he had committed a heinous crime, yet he was not what I imagined a murderer to look like. He was polite, well-spoken, and so friendly. If I ran into him in a dark alleyway at night, I would probably strike up a conversation similar to the one that we were having now, not run away in terror.

I would later find out that Brian has been in prison since he was 14 for killing a man. He is now in his early 30s. He will likely spend his entire life within the walls of OSP. I researched the Lifers Club at OSP after class had concluded, and learned it consists of men who have taken another person’s life, and feel they are forever indebted to society. “They recognize the harsh reality that the terrible acts of their pasts can never be erased or undone. They hope to use the long years in prison to come to terms with their histories and prepare for very different futures. The ledgers may never balance, but the club’s young officers share a deep belief that the Lifers owe a significant debt to society. They are focused on beginning reparations” (Inderbitzin, “Juvenile Lifers, Learning to Lead”). In other words, they are a group of men aiming to better themselves and the world to repay the harm they did, despite their confinement.

The following two and a half months that I spent with these men taking a course which examined our current education system were truly life-altering. Over the next nine weeks we covered a wide range of topics: the education system, the school to prison pipeline, racism in prison, restorative justice, and various life philosophies. These men shared the point at which they felt the education system failed them: when they dropped out of school, when they stopped caring, and when teachers stopped caring about them. We collaborated on homework assignments, and created works of art together. I was constantly amazed by the eloquence of my inside classmates. These men were considered to be societal failures and had committed some truly terrible crimes, but were so engaged in learning and brainstorming how we could change certain societal inequalities. We told each other small details of our lives, and formed many unlikely friendships; bonds that never could have occurred if not for this program.

We took a tour of the prison, and I stared inside the tiny shared cells these men called home. I stood in their cafeteria and listened as the guard giving us a tour explained the way the cafeteria was organized; that the men sat according to their race. “Whites are here, the Latinos sit back there, and the Blacks take up this side,” he had said nonchalantly. Later that day in class, my inside classmates told me they hadn’t realized racism still truly existed until they entered prison. On the same tour, I had walked past Death Row, and entered the death chambers. I am normally somebody able to keep my emotions in check, but as I stood staring at the straps that hold down a man’s arms and legs so he doesn’t resist while fighting for his last breaths, I nearly began to cry.

I formed a particularly close bond with one man whose nickname was Silver*. He killed two people at the age of 16, and will not be eligible for parole consideration until 2066. He is now in his mid-thirties, and is one of the most inspiring people that I have ever met.

He explained that when he first was sentenced to prison, he was outraged. He could not grasp the severity of what he had done, and did not believe that he deserved to be in prison. He told me how he used to run at the prison wall in the yard, in the hopes of jumping it. He was an angry teenager, unwilling to take responsibility.

And suddenly, a couple of years after he had been arrested, the nephew of one of the people he had killed wrote to him, asking him why he would do such a thing. Suddenly, the gravity of what he had done overcame him. The grief was so crippling that he became incredibly suicidal — but chose not to end his life because he did not want to cause any more pain to the people in his life who still cared for him. He explained to me that most people in prison follow one of two routes: they either give up, or persevere to make the most of the life that they have been given, even while imprisoned.

He began to vigorously work to change his character. While within prison he participated in a variety of different therapy groups, including anger management, grief therapy, anxiety therapy, and harm reduction workshops. He studied many different religions, and practiced meditation. Silver developed a love for poetry, and has used this gift to express himself since. The man I became friends with was an incredibly self-aware, empathetic and intelligent human being. Despite the atrocity he had committed, he had dedicated his life to bettering himself and trying to make a difference in the world in any small way he could. He would be a wonderfully positive role model to others, yet will live out the rest of his days within these cement walls.

Today, I prepare to re-enter prison and connect with my classmates for one final time. Inside-Out has a very strict no-contact policy in place; this means that under no circumstances am I allowed to contact any of my classmates again, for the rest of my life. When I began the class, I didn’t even question this policy. It seemed logical, and I couldn’t understand why I would want a continued relationship with somebody that I met inside of a maximum security prison. But then I formed deep, powerful connections with men who had against all odds tried to make efforts to turn their lives around, even while imprisoned. They were all taking this course for college credit, despite the fact that a handful of these men had life sentences and would never be able to utilize a college degree. Men such as Brian held leadership positions within clubs aiming to better society, although he would likely never re-enter society himself. I had formed meaningful relationships with the voiceless people of our society; the cultural underbelly. Considered to be the worst sorts of people, they are cast-aside and locked away. They are out of sight and out of mind, and those of us on the outside are not meant to give much thought to the imprisoned members of our communities. Legally, they are not allowed the same rights as those of us on the outside are allotted. It caused me to seriously question my inherent beliefs and what my idea of a “criminal” was. I was faced with the realization that for as open-minded as I like to think that I am, I am filled with unconscious biases and naturally stereotype others. My eyes had been opened to a part of our society that I had never had insight into, and I couldn’t imagine turning away now.

And yet, it is so complicated. On days when I eagerly awaited to see my inside friends, I couldn’t help but wonder how the families of their victims would feel. It brought up many questions for me, and I am still searching for the answers.

However, I did become sure of this: if the purpose of prison is to rehabilitate, that is not what it is accomplishing. Our system now is one of punishment, not of recovery and redemption. Men such as Silver and Brian could leave such a positive mark on our society today, but will likely never be given the opportunity to do so. And yet, they needed to be removed from society as juveniles.

It also reinforced for me that it is often not a person’s character, but their circumstances, that cause them to make terrible, irreversible decisions. Silver lost his parents and grandparents at a young age, and his adolescence was poverty-stricken, had limited supervision, and provided access to deviant peers entering a life of crime and gang violence. His upbringing does not excuse the fact that he took two young people’s lives, but I imagine that if he was raised in a safe, comfortable home with a loving family, he would not be confined to OSP today.

The stories of these men’s lives, the hopelessness of their situation, the pain experienced by the victims and their families, and the loss of my connection with them feels excruciating. Talking on the phone to my mother the week before my final day, I broke down crying in the middle of campus, as I prepared for this last class.

So today, I took a deep breath and walked into the classroom for the last time, smiling and searching for the faces of the men who had been frightening criminals nine weeks prior, but were now close friends who had irrevocably changed my life.

This is such an eloquent, compassionate tribute to the human beings who have been locked away from the world. Our prison system is based on so many old, outdated paradigms, and urgently needs to overhauled. (I am reminded of that horrifying statistic, that there are now more black men in prison than there were black American slaves.) Thank God this issue is on Obama’s radar now, too. But it it will be women like you, Hannah, who help us to see the human beings behind the statistics. Thank you for baring witness.

LikeLike